Try searching for “Reggae and children’s books” and you won’t find much. Try searching for “Rastafarianism and children’s books” and you’ll find even less. Even though reggae music and the Rastafarian religion are two aspects of a uniquely Jamaican culture, they are seldom written about in books published by mainstream publishers for children. Even nonfiction texts (the kind you find in libraries when looking for sources for your school report) about Jamaica give little attention to either.

With regard to religion, all of the nonfiction books I looked at begin with a phrase like the following, from Globetrotters Club: Jamaica by Michael Capek (Carolrhoda Books, 1999): “The British and Spanish colonists brought Christianity to Jamaica, where many African slaves began to practice the religion. These days, most Jamaicans are Christians”. While this may be true, it obscures the connection between colonialism and Christianity, and normalizes the Christian faith. African slaves in many cases “practiced” the religion because they had no choice. Today there are many sects of Christianity, some of which are more radical than others, but the photos in these texts that accompany a discussion of Christianity focus on well-dressed and orderly people. Only after establishing the dominance of the (apparently unified) Christian faith do they go on to discuss other religions, which range from Animism to Obeahism to Rastafarianism—which is usually listed last. The books for children seem to hesitate about how to discuss Rastafarianism, usually mentioning Haile Selassie and Africa, and commenting on the dreadlocks that Rastafarians wear. One of the commonly-known (though not necessarily understood) aspects of Rastafarianism, that of smoking marijuana, is treated gingerly if at all. One book, Sean Sheehan’s Cultures of the World: Jamaica, minimizes and criticizes the practice, suggesting that it is only a single sect of Rastafarianism involved with marijuana and “This sect is looked down on . . . because of its willingness to engage in the commercial distribution of marijuana” (79). Another of these books—Jamaica in Pictures, part of the Visual Geography series produced by Lerner Publications in the late 1980s, briefly mentions marijuana in connection with Rastafarianism, explaining somewhat obliquely that “Rastas share the belief that ganja (marijuana) is the biblical herb and the means of communication with God or of gaining insight or wisdom” (46).

Christians, well-dressed and orderly, on their way to church in Capek’s book. Rastafarians neither dress “properly”–nor go to church.

Reggae in nonfiction books about Jamaica is generally given a paragraph or less. Some books argue that it is in the tradition of the mento, or work song, because both used “music as a medium of protest and social commentary” (Jamaica in Pictures 49). Cultures of the World: Jamaica mentions reggae a lot more than other books, but this is because it connects it first with gangsters (38), urban ghettos (65), and Rastafarianism (78) before ever discussing its musical qualities. In fact, most books connect Rastafarianism and reggae together, even though Rastafarianism has been around since the 1930s and reggae only appeared in the late 1960s. (A clear example of the way these two have been connected in the public imagination is in the children’s picture book and animated series, Rastamouse, which has a reggae-playing, crime-fighting mouse band. I’ll discuss these books and the series in a later blog.) This connection comes largely from one man, Bob Marley, and nonfiction books almost never discussed either Rastafarianism or reggae until his death.

Despite Bob Marley’s importance to Jamaica, as well as to Rastafarianism and reggae music, and despite being well-known internationally, it is only relatively recently that picture book biographies of the singer have begun to appear. (I have found one, published by Hamish Hamilton and written by Chris May, from 1985, but this is for older readers.) I was curious about how much these picture books would address either Rastafarianism or reggae music, if they did so at all. I’ll focus here on two of these biographies, one written by Marley’s eldest daughter Cedella Marley and Gerald Hausman from 2002, and the more recent I and I: Bob Marley (2009) by Tony Medina.

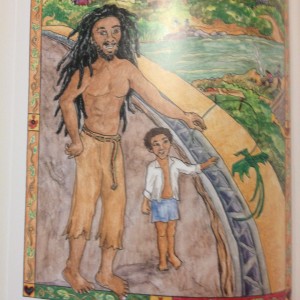

The Boy from Nine Miles by Marley and Hausman focuses on Marley’s very early years (the story ends when Bob Marley is seven); however, it does dwell on Marley’s musical beginnings and his connection to Rastafarianism. Like many of the nonfiction books about Jamaica, this book suggests that Marley’s singing career began with the folk tradition. The young boy would often go to Kingston Market and the market-sellers, or higglers, “did not only sell their things, they sang about them” (23), which later inspired Bob to do the same. In this same paragraph, the young Marley comes across a “blackheart man” who initially inspires fear, but who turns out to be “soft-spoken and nice”. By looking at the book’s glossary, a child reader can find that blackheart man was “An old way of saying Rastafarian” (48). The story’s text uses neither of the terms reggae nor Rastafarianism, but the inference is of a singer, connected to the working people’s song tradition, who sees Rasta men early on as nice rather than threatening. This image is repeated in Medina’s I and I, with its gorgeous illustrations by Jesse Joshua Watson, where the young Marley is in the Kingston Market, this time being served by a singing Rasta haggler.

Now the Blackheart Man becomes the singer as well; Watson’s illustration for I and I unites reggae and Rastafarianism

The book goes further in Marley’s life, and so both Rastafarianism and reggae are specifically mentioned. Medina’s biography is written as a series of poems, and “I am a Rasta Man” makes the connection between Rastafarianism and reggae explicit. The poem, written in Marley’s voice, proclaims, “A troubadour for the common man/ Singing what a Rasta sings/ Reggae music from/ My guitar strings” (n.p.). Medina goes on to describe Rastafarianism in the poem, connecting it with Africa and Haile Selassie as the nonfiction books do, but also adding it is a religion of peace and love. Reggae music embraces that message, but also adds a political dimension; in the poem “Reggae,” Bob and Rita Marley are dancing in a club to reggae music—seemingly an apolitical activity—but in the midst of the “sweet” beats, “We sufferers we shufflers/ Party to the music/ Of our hopes and dreams/ Chantin’ down Babylon/ All night long” (n.p.). While still sticking to the more socially acceptable aspects of both reggae and Rastafarianism (with nary a word about marijuana or gangs, for example), Medina’s book allows for Bob Marley to be both a Rasta Man and a Reggae Man—and present these things as something that child readers can admire.

We had the Boy From Nine Miles in our school library and I found it very interesting but wished to know more.

LikeLike

I still want there to be more for kids to read about Bob Marley!

LikeLike

We need more Rastafarian children’s books and Jamaican fairytales.

LikeLike