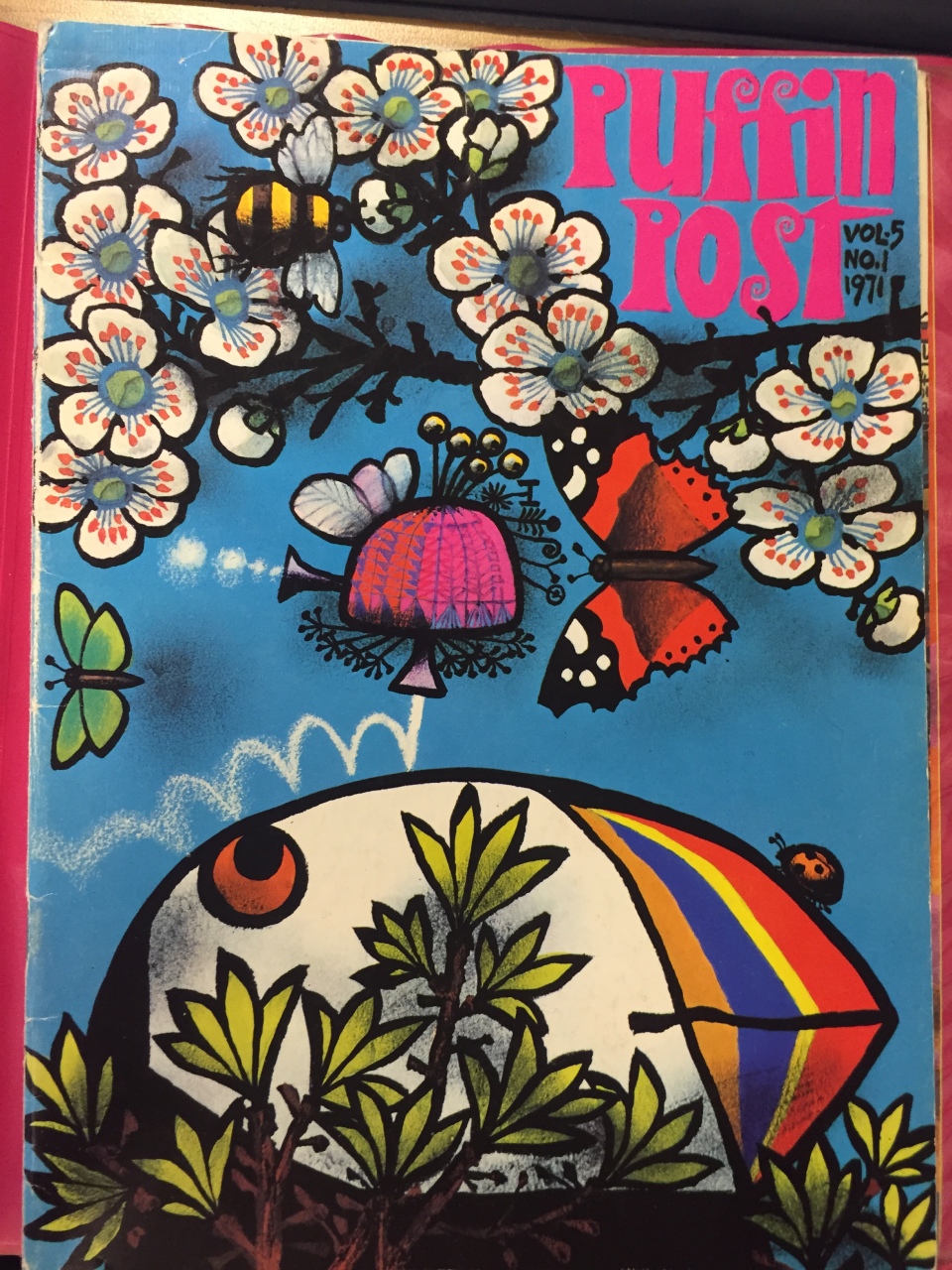

While I was researching at Seven Stories this past year, I started doing an inventory for them of books in their collection that had non-white authors and characters. They have a generous amount, so I didn’t finish the list, but I did get through a collection of Puffins while I was there. Puffins, the juvenile imprint of Penguin, had their heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, when books were cheap and middle class aspirations were high. Puffin even ran a club, with magazines (including games, book excerpts, and advertisements for new Puffin titles) and outings to places like the Whipsnade Zoo. The magazine is revealing, because it includes photographs of young Puffin Club members at author events and outings. Despite paging through a couple of decades of the Puffin Post, I did not find a single non-white face in the club member pages.

The Puffin Post contained stories, games advertisements for new Puffins and puzzles–and photos of its members.

This does not necessarily suggest there were no Black or Asian Puffin Club members, but it does indicate that the audience for the Puffin Club and Puffin books was largely white (and, in order to be able to afford outings and yet also find them novel and exciting, probably middle-class white in the main). But the books that Puffin published were not exclusively about white Britons during this time period. Most famously, perhaps, Puffin did the paperback edition of Bernard Ashley’s The Trouble with Donovan Croft in 1977 (and then in several reprints with different covers). This is a book focalized through the white character about his mute Black foster brother, Donovan Croft. Puffin also published other contemporary stories with Black British characters, including Geoffrey Kilner’s Jet: A Gift to the Family (1979), also (like Donovan Croft) by a white author; and reprints of books by West Indian authors Andrew Salkey and James Berry—although these were set in Jamaica.

![IMG_2682[1]](https://theracetoread.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/img_26821.jpg?w=960)

The 1977 Puffin cover of Andrew Salkey’s Hurricane, from artist Julek Heller, contains nothing to indicate its Jamaican setting.

![IMG_2681[1]](https://theracetoread.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/img_26811.jpg?w=960)

Puffin’s cover for Sophia Scrooby Preserved, illustrated by David Omar White.

And there were reasons for Puffin to choose Scrooby. First, it has an element of adventure, since the book starts with the main character—who would eventually be renamed Sophia Scrooby—in her African village, which is burned to the ground by another African tribe. The girl escapes and lives with impala for a while before “accidentally” becoming enslaved when looking for food. She is taken to colonial America, just before the Revolution, and lives with a family of royalists who treat her like family and teach her Latin and to sing operatic arias. Unfortunately, they “accidentally” forget to free her, so that when they are driven out of their home by creditors, Sophia has to be left behind with the goods to be sold. After a number of adventures, during which she preserves her French lace dress and the necklace she wears, and is never once beaten or struck, she ends up escaping once again (this time from a “West Indian voodoo queen” in New Orleans) and goes to Britain. Upon setting foot on English soil, she is treated like royalty and goes to live with a rich old lady as her companion. In London she meets no less than Ignatius Sancho, the composer and anti-slavery companion. Sancho discovers she is from London and complains, “I cannot countenance rebellion. Better to make peace and pay her taxes and free her slaves” (206). This is some forty years before Britain “frees her slaves”, but as with the bad Victorian history textbooks, Bacon’s text assumes that because Britain has passed the Somerset Ruling, all of Britain’s slaves are now free.

Bacon’s book was one that worked for Puffin, because it contained all the elements of an exciting adventure story, as well as being on “the side of the angels” politically at a time when a growing population of Black British students were being told that West Indian students couldn’t learn in the British school system or integrate into British society. Sophia Scrooby Preserved presents a picture of a well-dressed, well-spoken, independent African girl in London who can earn her own living and move in society’s circles. Sadly, what Sophia Scrooby preserves is the idea that the white British were innocent of the brutality of slavery.