There are two kinds of racism: incidental, by which I mean something that happens because of the actions of individuals; and systemic, by which I mean the deep-rooted, institutionally-supported disadvantages experienced by people of color. These two racisms are not mutually exclusive; often, someone feels that their individual racist comment or belief is justified because the system or society does not censure their speech or action. Equally, if individuals were more willing to examine and censure the individual racisms of themselves and those around them, systemic racism would begin (or at least be easier) to break down. But they certainly manifest in different ways.

Anne Rooney’s Race Hate tries to take a balanced approach by interviewing racists. But Race Hate is apparently an individual, rather than an institutional, problem.

This week, news items in the UK and US showed both kinds of racism. In the UK, what seem to be examples of incidental racism actually point to systemic problems. And in the US, a result that seems to suggest systemic problems highlights the responsibility of individuals. Bonfire Night in the UK saw one group of people delighting over the burning of a model of Grenfell Tower (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/grenfell-tower-model-bonfire-burned-guy-fawkes-party-a8618661.html), and a Tory councilor wearing blackface at a Bonfire Night event in Hever (https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/nov/07/tory-councillor-wears-blackface-kent-bonfire-celebrations). These were both roundly condemned in the media and the public, as well as by officials. Theresa May criticized the Grenfell Tower bonfire. And yet, her condemnation was called out by several people who pointed out that many Tower residents are still unhoused nearly a year-and-a-half after the fire (see, for example, Nikesh Shukla’s tweet from 6 November 2018). The bonfire was unacceptable racism; but the system that allows the people of Grenfell Tower to continue to suffer at the hands of the government is not changed. Similarly, the Tory councilor was participating in the bonfire as a member of a Church of England school PTA. The school dissociated itself from the incidental racism, saying, “We are very proud to be a multicultural school with ‘respect, love and wisdom’ as our motto” (Guardian online); but they failed to acknowledge their responsibility to ensuring that all members of their community—PTA included—embraced the slogan. Neither the government nor the church created or directly encouraged the individual racist behavior. But the government’s and the church’s own lack of action on racism makes it easier for racists to act.

“People may have racist ideas instilled in them”: but who is doing the instilling?

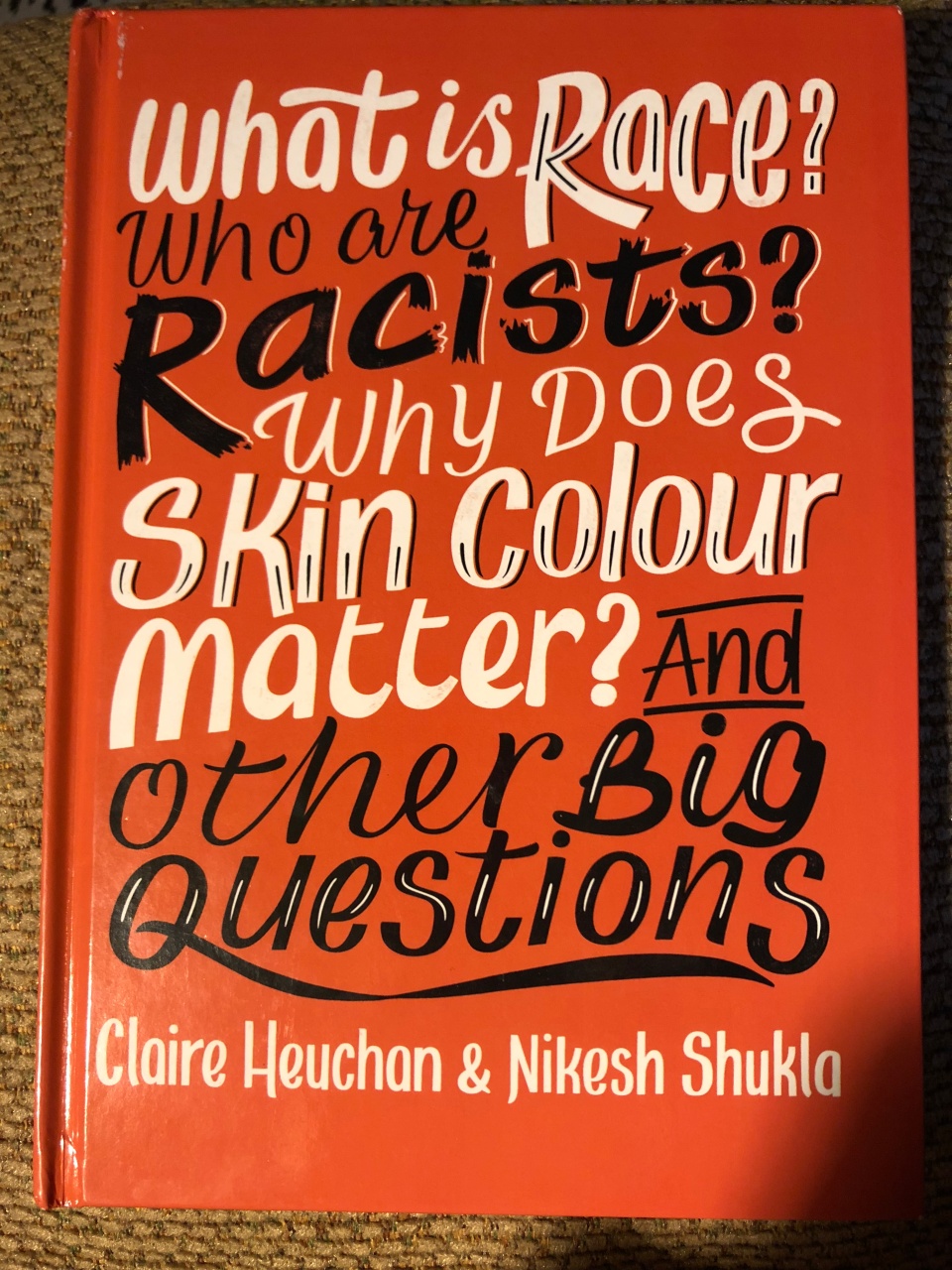

Children’s books, even well-intentioned ones, do not always make this link between individual acts and institutional racism. Anne Rooney’s Voices: Race Hate (Evans Brothers 2006) is part of a series which, according to the back cover, “brings alive a range of modern-day issues—many of them highly controversial—and aims to stimulate debate and discussion.” Although I am not convinced there is much that is “highly controversial” about any kind of hate (hate is something we tell children is bad, no?)—not to mention the lack of controversy about the issue of hunger or child labour, other titles in the series (also bad, no?)—this series is clearly designed to discourage, rather than encourage, readers’ participation in or support of these issues. But by failing to address the link between systemic racism and individual acts, the book ends up excusing people from the responsibility for racism. Thus, the double-page spread, “Why Hate Other Races?” excuses individuals from racism by blaming “stereotypes” without explaining that stereotypes are connected with systemic, structural and institutional racism. The photo on page 9 includes a caption that says, “Many white families employed black workers to serve them” but does not connect this servitude with a history of slavery, or a lack of other available employment opportunities for Black people. Claire Heuchan and Nikesh Shukla’s recent book, What is Race? Who are Racists? Why does Skin Colour Matter? And Other Big Questions (Wayland 2018) addresses this failure to link structural and individual racism head on, pointing out the consequences of such a failure: “Even when people are aware of racism, they can hesitate to point it out because of the implication that somebody has been racist . . . So we end up in a strange situation where there is racism but, supposedly, no racists. Except racism is produced by people who are racist—so if we are ever to pull apart the racist structures of our society, there must be a way to say who is propping them up” (6).

Heuchan and Shukla’s book recognizes that institutional and individual racisms matter.

While individual racist acts exposed systemic problems in the UK, the news from the US this week highlighted the opposite problem. One of the headlines of this week’s midterm elections was the record number of women who ran and won in their races. Some media even called the elections the #MeToo Midterms (https://thehill.com/homenews/house/406183-women-wield-sizable-power-in-me-too-midterms), and election reports frequently mentioned the “suburban women” who helped defeat Trump-approved candidates. Of course there is nothing racist in women running and supporting candidates for office (indeed, many of the new congresspeople are women of color). But “suburban women” is media code for white women (here’s one report on “suburban women”: https://www.msnbc.com/stephanie-ruhle/watch/how-will-suburban-women-vote-in-the-midterms-1358101059960?v=railb&), and the #MeToo movement (which was started by an African-American woman) has been criticized for its focus on white women as well. Just as second-wave feminism was about the middle-class, educated white woman, excluding and eliding the rights of women of color, the midterm elections reveal that white women will unite around an issue that directly affects them, but cannot extend their understanding of oppression to issues such as police brutality against African-Americans or racist and jingoistic language and threats against migrants and refugees. The system allows racism to exist, and white women—who understand what it is like to be oppressed by that system—do not, through their individual votes, call for an end to that system.

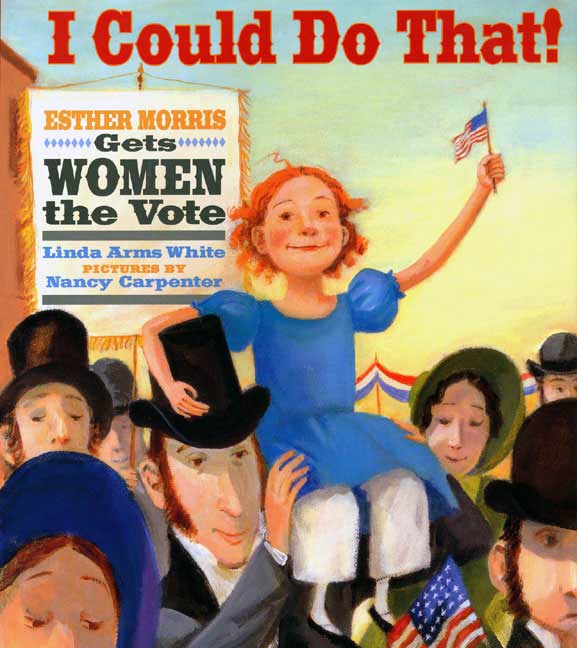

Curiously, even though White’s book mentions both abolition and the civil war as causes Morris supported, there is not a single African-American depicted in the book.

Again, even well-meaning children’s books can sometimes reinforce systemic racism (and classism) under the guise of individual choice. Most children’s books about women’s suffrage show photographs of white women only, and have lines like, “only men can vote” (I Could Do That! Esther Morris Gets Women the Vote, by Linda Arms White, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux 2005). This elides the fact that in America, African-Americans could not vote, and in Britain only rate-paying men could vote until 1918, the same year that women over 30 got the vote. An alternative approach can be found in Nosy Crow’s short story collection, Make More Noise: New Stories in Honour of the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Suffrage (2018). Unlike many books about women’s suffrage, which focus almost exclusively on white women and their struggle, Make More Noise includes stories about all kinds of women and girls, historically and contemporaneously. Patrice Lawrence’s story, “All Things Bright and Beautiful,” for example, tells the story of Olive Malvery, a woman of English and Indian parentage, who “came to London when she was twenty-three and was shocked by the way poorer women were treated” (83). Lawrence’s story shows Malvery helping a young mixed-race girl who suffers not just from being poor, but from being brown. When the young girl, Victoria, asks for an extension on her rent, her landlady tells her, “the best thing your father could have done was take you with him back to whatever country he came from!” (59). This and other stories in the collection show that no woman has an identity based entirely on gender—so all women should band together to ensure everyone’s rights.

Nosy Crow’s Make More Noise listens to the noise of all kinds of women, not just white suffragettes.

Racism is, or should be, unacceptable to people of all backgrounds because it harms the entire society. But if we can’t recognize our individual racism, then we can’t fight systemic racism. And if we don’t see the systemic, structural and institutional ways that racism is supported, then fighting individual racism will never lead to victory. Racism will go on being acceptable, and we will all be the worse for it.