Do you remember playing a game, maybe at a birthday party, called Statues? You took a statue pose and had to be the last one remaining still. You often got a prize for not moving. I had this image in mind over the last few days, as the events in Charlottesville had people all over the world focused on the way that statues can take us back in history and hold us in a place of racism, division, and oppression.

I’m not the only one who has been thinking about this. London’s Black History Walks group (http://www.blackhistorywalks.co.uk/) has a list of eight statues and buildings with racist histories in the UK (you can sign up for their email newsletter even if you are outside the UK to get this and other stories, but if you can get to one of their history walks, I can personally recommend that you do so). And of course there is the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, which began in South Africa in 2015 and expanded to Oxford in 2016; this week the global editor of the Huffington Post, Lydia Polgreen, commented on Rhodes Must Fall as a model for Americans who want to remove confederate statues, although she added, “changes to monuments will only be enough once economic justice is included in the redress of South Africa’s socio-economic crisis” (http://www.huffingtonpost.co.za/2017/08/14/rhodes-must-fall-campaign-could-help-charlottesville_a_23076674/). There have been many critics of the idea of statue removal as well. I doubt I need to tell you who was “sad” this week “to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments,” but he is not alone in this sentiment. Many have suggested that statues of racist and imperialist figures in statues and monuments remind us of humanity’s troubled past, and help keep us from repeating mistakes (although the logic of this when examined in light of this week’s events is somewhat questionable).

But surely, even if you believe that statues can tell a sobering history of human inhumanity, that story must be put into context; otherwise, viewers draw their own conclusions. Many towns, for example, have statues of generals in full battle gear in triumphant poses, but only simple pillars or crosses to the many ordinary soldiers that died in the battle or war. To me as a child, that always suggested that generals were heroic and important, but you should definitely try not to be an ordinary soldier, since their lives clearly did not matter as much. There was no context to tell me anything different, especially before I could read. Image was everything.

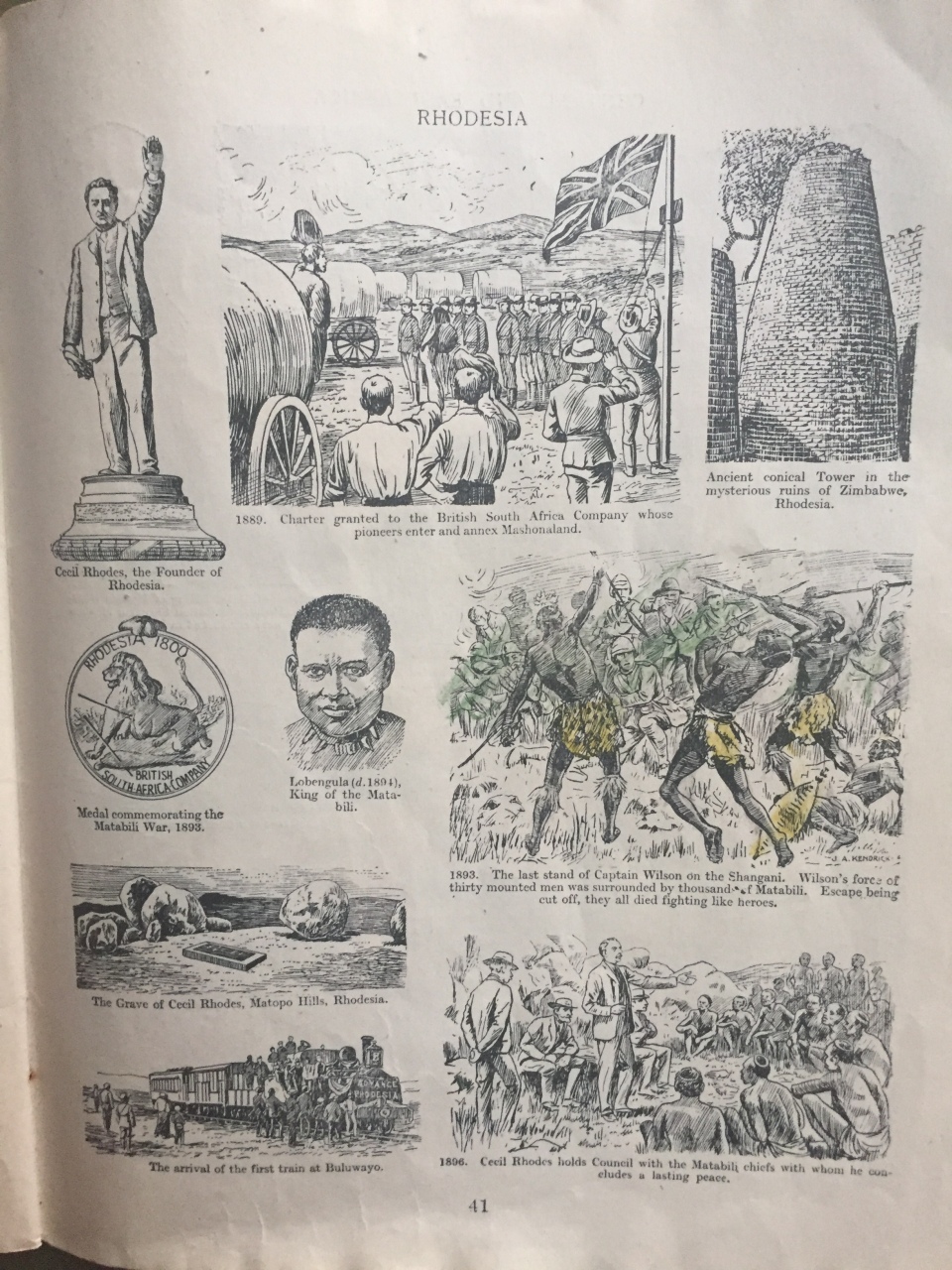

CW Airne’s Our Empire’s Story shows a triumphant statue of Rhodes. Note that even in the depiction of the Last Stand of [white British] Captain Wilson, it appears the Matabili are losing.

Taking a stand against imperialism and slavery; Morrison’s Guyana celebrates Cuffy rather than Victoria.

I was therefore quite surprised to examine more modern examples of geography texts and see how other histories often take pride of place. My collection only includes a small sampling of geography texts about the West Indies (my particular area of interest) but the books I do have either ignore statues and monuments altogether, or highlight anti-colonial histories through their statues. Marion Morrison’s Guyana (Children’s Press, 2003), part of the Enchantment of the World series, does not mention the famous statue of Queen Victoria, erected in 1887, dynamited in anti-colonial protests in 1954, and finally permanently removed in 1970 upon declaration of the Guyanese republic (http://interactive.britishart.yale.edu/victoria-monuments/210/statue-of-queen-victoria-), but has a photograph of a statue of the Berbice Rebellion leader, Cuffy (48).

Martin Hintz’s Haiti (Children’s Press, 1998) in the same series, not only has a picture of the statue of King Henri Christophe (22), but also includes an undated historical drawing of “A temple honoring the end of slavery at Le Cap” (85).

Sarah De Capua’s Dominican Republic (Marshall Cavendish, 2004) is perhaps the most disappointing of the books I found with statues. Part of the “Discovering Cultures” series, the book not only elides Columbus’s connection with the slave trade on the page that shows his statue (11), it fails to discuss the front cover statue, the Monument of the Heroes. Originally a statue to the dictator Trujillo, the statue was repurposed to depict heroes of the war of independence from Spain in 1961. But nothing about the statue is mentioned in the text, while Columbus is depicted as the founder of the first permanent colony in the island.

Malcolm Frederick’s Kamal Goes to Trinidad (Frances Lincoln, 2008), with its pictures by Prodeepta Das, could also have included a photo of the statue of Columbus that stands in Port of Spain, but instead, he chose a statue that acts as a reminder of both the British Empire and a time more than a thousand years’ previous (when Britain itself was a tiny outpost of the Roman Empire). The inclusion of the statue of Hanuman, the Hindu deity, points out Trinidad’s multiculturalism that resulted from British imperialism—but the religion itself came before and outlasted that empire.

Statues depict a moment in time to remind people of historical events. They can act as a way to glorify a less-than-glorious history, especially when viewed without a context (or with a one-sided context). But as some of these examples from children’s geography show, statues can, paradoxically, show us a way to move away from histories of racism and imperialism, and toward one of ordinary people’s struggle against that oppression.