Yesterday was Roald Dahl Day—really just his birthday, but a day that is celebrated in the UK with, well, a lot of Dahliana (yes, I did just make that word up). Dahl is one of those writers whose books incite both passion and disgust (the latter mostly from adults, who are frequently targets of criticism in Dahl’s writing). As Peter Hunt put it in The Cambridge Guide to Children’s Literature, “Although he claimed to be on the child’s side he has been widely seen as manipulative, and has been accused variously of racism, anti-Semitism, misogyny and cruelty. On the other hand, his supporters (who far outnumber his detractors) argue that he speaks to childhood values (such as love of simple justice), and to children’s delight in excess, cartoon-like extravagance, and verbal ingenuity.” You can guess from this quotation where Peter falls on the scale of Dahl appreciation (his use of the word “claimed” is almost New Testament in nature). I, on the other hand, grew up with Dahl and he was even a part of our family jokes; my dad used to say, “Hush, Veruca,” to me when I was acting spoiled. And even now, there are a few people I wouldn’t mind seeing squashed by a giant peach.

I’m sure I never acted like this, dad! Julie Dawn Cole plays Veruca Salt in the 1971 film version of Dahl’s book.

But even as a kid, there were things that bothered me about Dahl’s books, and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) in particular. For example, was chewing gum really equivalent to gluttony, greed, or even watching too much television? And the Oompa-Loompas made me uncomfortable (although I did like some of their Greek-chorus-like pronouncements): why were they all men? Why were they all tiny? Why did everyone, the Oompa-Loompas included, think that it was okay for them to be held captive in Wonka’s factory?

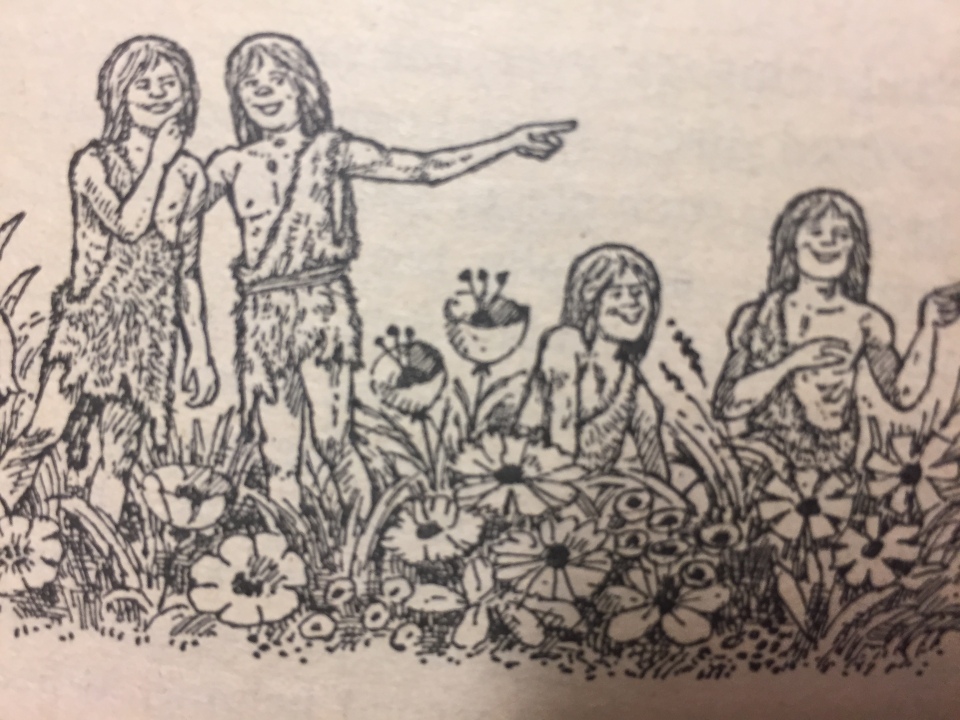

Troublesome issues, even for a child: Joseph Schindelman’s drawing of gum-chewing Violet being rolled away by the Oompa-Loompa “pygmies”.

One thing I never questioned as a child was Charlie’s ethnicity. Partly this was because he was British; as far as I knew growing up in America, British people were white. But more to the point, book characters were white, especially book heroes. There was an occasional exception to this rule—Mildred Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear my Cry (1976) springs to mind—but these were usually books that were ABOUT being a Black person and/or encounters with racism. Books about “ordinary” things like magical people only ever included white people.

A case of “reading while white”? Although Ursula LeGuin’s 1968 novel features a hero with red-brown skin, many readers, used to white heroes, didn’t notice.

Yesterday, however, that notion was challenged by Roald Dahl’s widow, who commented on Radio 4 that Dahl originally intended Charlie to be Black British but he changed his character (according to Dahl’s biographer, Donald Sturrock) because his agent said people would question the decision (http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-41257684). It certainly would have raised eyebrows in 1964, when characters in British children’s books were not quite all as white as American readers might have thought, but when most Black British characters were still contained in “issues” books. This point is underscored by Liccy Dahl’s follow-up comment that she was sure Dahl’s desire to make Charlie Black British “was influenced by America”; despite Britain’s changing population in the 1960s, many white people still connected Black people with America and not their own country.

![IMG_2702[1]](https://theracetoread.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/img_27021.jpg?w=960)

Charles Keeping did not hesitate to make one of his characters Black British.

Faith Jaques’ revised (1973) illustrations of the Oompa Loompas do not erase all of the problems of representation.

Additionally, the suggestion that Dahl wanted to include a Black British Charlie has to be balanced with his troubling portrait of the Oompa-Loompas, something with which his agent was apparently entirely comfortable. The original Oompa-Loompas were Black; Wonka tells his guests, “Pygmies they are! Imported direct from Africa!” (65). Later editions (including the one I read as a child) changed their origin to the vaguely less problematic “Loompaland” but didn’t change the circumstances in which an entire people were removed from their homeland to live entirely in captivity. As Clare Bradford has pointed out, “Dahl’s portrayal of the Oompa-Loompas is oblivious to the wider implications of a group of immigrant workers exploited by a factory owner” (The Routledge Companion to Children’s Literature 39).

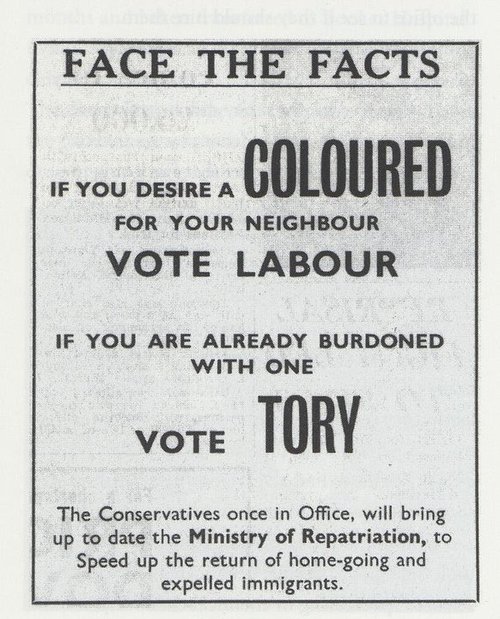

A “tame” version of the Smethwick campaign slogan widely reported on in 1964, the same year as Dahl’s book.

Given that the book was published in the same year as the infamous Smethwick election wherein one candidate used the slogan, “If you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Labour” (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/15/britains-most-racist-election-smethwick-50-years-on) and two years after the first Commonwealth Immigration Act restricting “coloured” immigration, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is oblivious about more than just immigrant exploitation. Dahl may have had good intentions about including the wider world in one of his most famous books, but the result is as disappointing as opening a Wonkabar and realizing you haven’t found a golden ticket.