This is refugee week, as well as Windrush week, in the UK, and I wanted to combine those two events by continuing my thinking about the Declaration of the Rights of the Child. This week my focus is on Principle 7, which states that “The child is entitled to receive education which shall be free and compulsory, at least in the elementary stages. He shall be given an education which will promote his general culture and enable him, on a basis of equal opportunity, to develop his abilities, his individual judgement, and his sense of moral and social responsibility, and to become a useful member of society.” In Britain, the first part of this is and has been done, for citizen, immigrant, and refugee alike. But the second half of the statement, about an education that promotes the child’s culture and sense of self, has been much more difficult to achieve for newcomers to Britain.

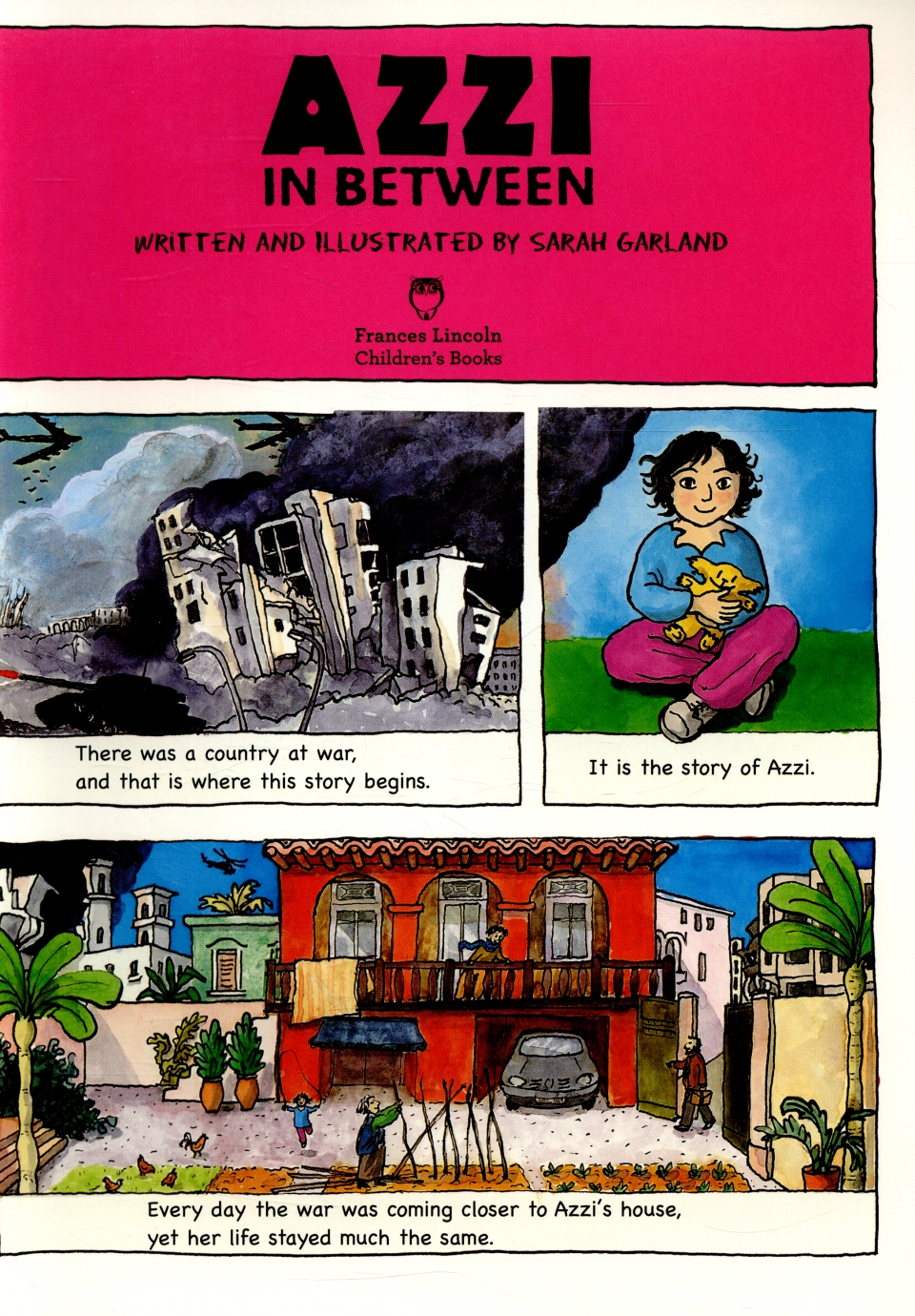

Bernard Coard’s book highlighted the plight of the Black child in British schools in the late 1960s and early 70s–and led to an increase in supplementary education.

In the late 1960s, the children of the Windrush generation—some of whom had come to Britain after their parents got settled, and some of whom were born in the country—began attending British schools in large numbers, particularly in the urban centers of London, Bristol, Birmingham and Manchester. Many schools struggled to accommodate them. Arguing language difficulties, behavioral problems, and lack of preparedness for school, teachers placed a considerable percentage of Black children (particularly boys) in what were then called ESN (Educationally SubNormal) classrooms. This was meant to be a temporary measure for most children, but many never left the ESN classrooms, and left school without qualification or skills—sometimes not even knowing how to read—because of it.

The official line from the British government was that these children should assimilate into British society, and accept British customs and traditions. But parents of Black British children saw the situation differently. They felt that it was because their children were being asked to give up their culture and not taught their history that they were disinterested in school. Many of the parents had come to Britain to give their children a better chance at education and they weren’t going to watch them lose that chance because the government felt that their children ought to be just like white Britons. Through organizations and movements such as the Black Parents Movement, the Caribbean Education and Community Workers Association, and the Anti-Banding Campaign, Black parents worked together to provide the missing piece of education for their children: the culture and history of their own people. Bernard Coard’s How the West Indian is Made Educationally Sub-Normal in the British Schools, published by Black British publisher John LaRose in 1971, gave parent groups the impetus and the statistics they needed to organize and fight for their children’s rights to maintain a sense of pride in their culture.

John LaRose, who helped start the George Padmore school, and Jessica and Eric Huntley, who were involved with the Marcus Garvey school and later the Peter Moses school, published children’s books and supported those who did. Photo from “I Dream to Change a World” exhibition in 2015.

Since they generally could not get the schools to teach Black history and culture (and to be fair, most white British teachers had never been prepared to do so), Black parents set up a number of Supplementary Schools: local, after school or Saturday programmes staffed by some trained teachers and many more interested but untrained parent volunteers. Some of these schools had only a few children; others had fifty or more. The George Padmore school, started by John LaRose in his own living room, began with only four children: his own two sons, and two of their friends. But large or small, the critical element was improving the experience of Black children in the British schools. Initially, the supplementary schools concentrated on what one school, the Marcus Garvey school in Shepherds Bush, called “simple MATHS and elementary ENGLISH” (note to parents, found in the London Metropolitan Archives, LMA/4463/D/01/006) because the children were so far behind their white counterparts. But even early on the supplementary schools wanted to improve the children’s sense of self; John LaRose, writing about the founding of the George Padmore school in Finsbury Park, said that the late 1960s “was a time when anxiety about the education system in Britain and what it was doing to black children had already surfaced . . . the schools gave black children no understanding of their own background history and culture and no help in understanding their experience of the society in Britain” (George Padmore Institute Archives, BEM 3/1). One of the important ways that supplementary schools helped Black children develop a sense of identity was through a study of their history and culture in their reading material.

Longmans history of Equiano was used by the George Padmore school. Illustrated by Sylvia and Cyril Deakins.

We can get a look at that reading material because fortunately, some of the schools kept records of the books they used. Many schools included biographies, from the self-produced biographies of Caribbean figures like Alexander Bustamante at the George Padmore school to standardized educational biographies (the George Padmore also used biographies of people like Wilt “the Stilt” Chamberlain from the American group, Science Research Associates or SRA, which produced a graded reading scheme in the 1960s and 1970s that I used in my own childhood). Some of the material came from mainstream publishers, such as John R. Milsome’s biography of Olaudah Equiano: The slave who helped to end the slave trade (Longmans 1969) or Phyllis M. Cousins Queen of the Mountains (jointly published by Ginn and the Jamaican Ministry of Education 1967, about Nanny of the Maroons).

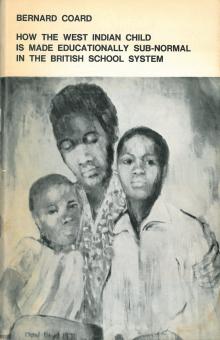

The publishers Ginn and Co. worked with the Jamaican Ministry of Education to produce this biography of Nanny of the Maroons. Illustrated by Gay Galsworthy.

The fact that Queen of the Mountains was a joint publication between Ginn and the Jamaican Ministry of Education was important, because much of the history used by supplementary schools was not available in British textbooks. Supplementary schools had to look back to the Caribbean for reading texts that reflected their own children’s history and culture as well. Although several reading schemes, including Leila Berg’s Nippers published by Macmillan and the Breakthrough series published by Longman, did by the early 1970s include Black characters in some of their stories, very little reflected the traditions or a positive view of the contemporary Caribbean. This may be why the George Padmore and Albertina Sylvester School (the two schools combined to share resources) used reading texts from the Caribbean, such as Inez M. Grant’s The Island Readers from Collins and the Jamaican Ministry of Education instead of British readers. In reader 2A, Stories for Work and Play (1966), children in the supplementary school could read about the modern manufacturing of condensed milk in Jamaica, as well as the traditional celebration of John Canoe—which came originally from an African source. In this, the Black British child had his or her culture supported, and have a firmer foundation on which to build a future.

An illustration of the John Canoe celebrations by Dennis Carabine for Inez Grant’s story, “Betty and Harold see John Canoe” in the Island Readers Stories for Work and Play.

The supplementary school was an important feature of Black British life in the 1970s and beyond (many still are running today). It led me to wonder if refugee or other immigrant children might be having similar issues as Black children had in the 1970s—and whether book publishers might think about ways to support them in understanding their past, present and future through books that recognize and celebrate their culture.