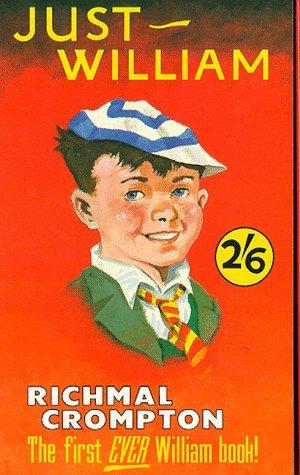

The original Just William, illustrated by Thomas Henry.

The other day in the British chain bookshop, Waterstone’s, I was startled to see Richmal Crompton’s Just William change skin color. The mischievous scamp, whose fan site calls him “one of the most popular fictional characters of all time” (http://www.sharpsoftware.co.uk/william/) first appeared in 1919 in Home Magazine; some of the stories that appeared there were collected into a book, Just William, in 1922, and the character lasted through 38 books—the last of which was published in 1970, a year after Crompton’s death. Films were made in the 1940s, and television series in the 1970s and 1990s. In all of these incarnations, William was white. Yet here he was, staring out from the cover illustration of Still William (the eighth book in the series, originally appearing in 1924), brown-skinned and spiky-haired.

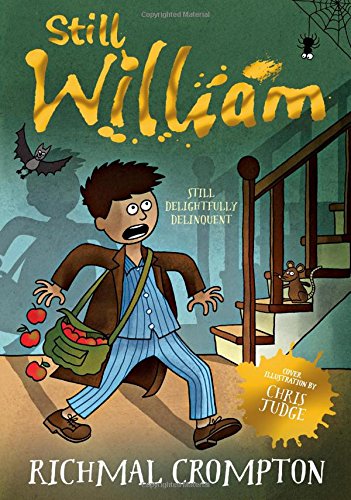

A browner version of Wills in the new cover by Chris Judge from Macmillan.

Macmillan, who reissued the early books in the series, had several guest illustrators design the covers. Chris Judge’s cover of Still William is the only one to imagine a non-white William, but he doesn’t comment on this in his back cover blurb, saying only, “The Just William series of books was my dad’s favourite growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, and there were always beautiful, well-thumbed editions of them on every bookshelf in my own youth. It is such a joy to get to illustrate a new cover for something that meant so much to my dad as a boy.” Unfortunately for readers attracted by this reimagined William, the book’s inside illustrations are the original drawings for the book by Thomas Henry; after a brief moment as a non-white character, William returns to “normal”. Judge’s cover may have been an acknowledgement by Macmillan that the audience for the William stories might have changed since their inception, but the idea of a whole book-ful (not even a whole series-ful) of non-white William is still a bridge too far.

Revising children’s books to reflect a changing audience is not a new concept for children’s publishers. Children’s versions of the Bible story Noah’s Ark used to provide a case for the enslavement of Africans, because Noah’s youngest son—who was, according to these stories, dark-skinned—laughed at his father for getting drunk and was subsequently banished. This, needless to say, is no longer the emphasised element of the story. More recently and controversially, Hugh Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle and the first edition of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory famously both underwent revisions when publishers found their original texts too racist. (I would argue that both texts maintain a strong sense of white privilege and/or superiority, even in their expurgated versions; Willy Wonka may have been a benevolent Oompa-Loompa controller, but the “tribal people” still never left that factory and weren’t paid except in food and housing.) These cases drew considerable attention because the author’s words—and, presumably, their intentions as well—were changed. (And, at least in the case of Lofting, he wasn’t around to defend himself or protest the changes.) Phil Nel writes about these two books here http://www.philnel.com/2010/09/19/censoring-ideology/ if you want to read more, but the point I’m making is that publishers have a lot of power when it comes to what children get to see in children’s literature.

Three different covers for Enid Blyton’s Happy Day Stories, 1960, 1969, and 1973.

And sometimes they get it wrong. Enid Blyton’s books often have come under scrutiny for various politically incorrect attitudes, but in 1969, the publishers Evans made a problematic story worse by changing the cover. The original hardback version of Happy Day Stories was published in 1960, and had a picture of a blond boy writing on the cover. Perhaps in a recognition of the changing British population in the 1960s, when thousands of West Indian families came to Britain to settle, they changed the cover for the paperback edition. The new cover illustrated a story called “Alice-all-alone” in which a young loner named Alice learns to socialize when she believes her “golly” has come to life. It turns out that actually the “golly” is the kid next door, who has gone to a fancy dress party dressed up as a golly (the logic required to make this work is beyond me). The picture on the cover shows the boy, in blackface but still clearly not of African descent. Alice in her swinging sixties outfit appears puzzled but intrigued.

I have no idea how this book sold, but just a few years later, Evans revised the paperback cover yet again. This time they chose (wisely) a different story for the cover, a story in which “The Three Bad Boys” are stuck up a tree by the threat of goats. Although in the original story, Len, Harry and Jack are white, the 1973 cover makes one of the boys non-white. Both covers are by the same illustrator, Marcia Lane Foster, but the second is far less problematic. Nonetheless, I’m not sure whether either cover—or any other marketing tool—could make some of the Enid Blyton stories palatable to a Black British audience.

So to return to Macmillan, Just William, and Chris Judge, I was certainly intrigued by the idea of Judge’s rethinking of a classic character. But I worry that, like Macmillan, readers will only give momentary thought to the idea of an alternative version of a classic before returning to the comfortable, all-white world of children’s classics.