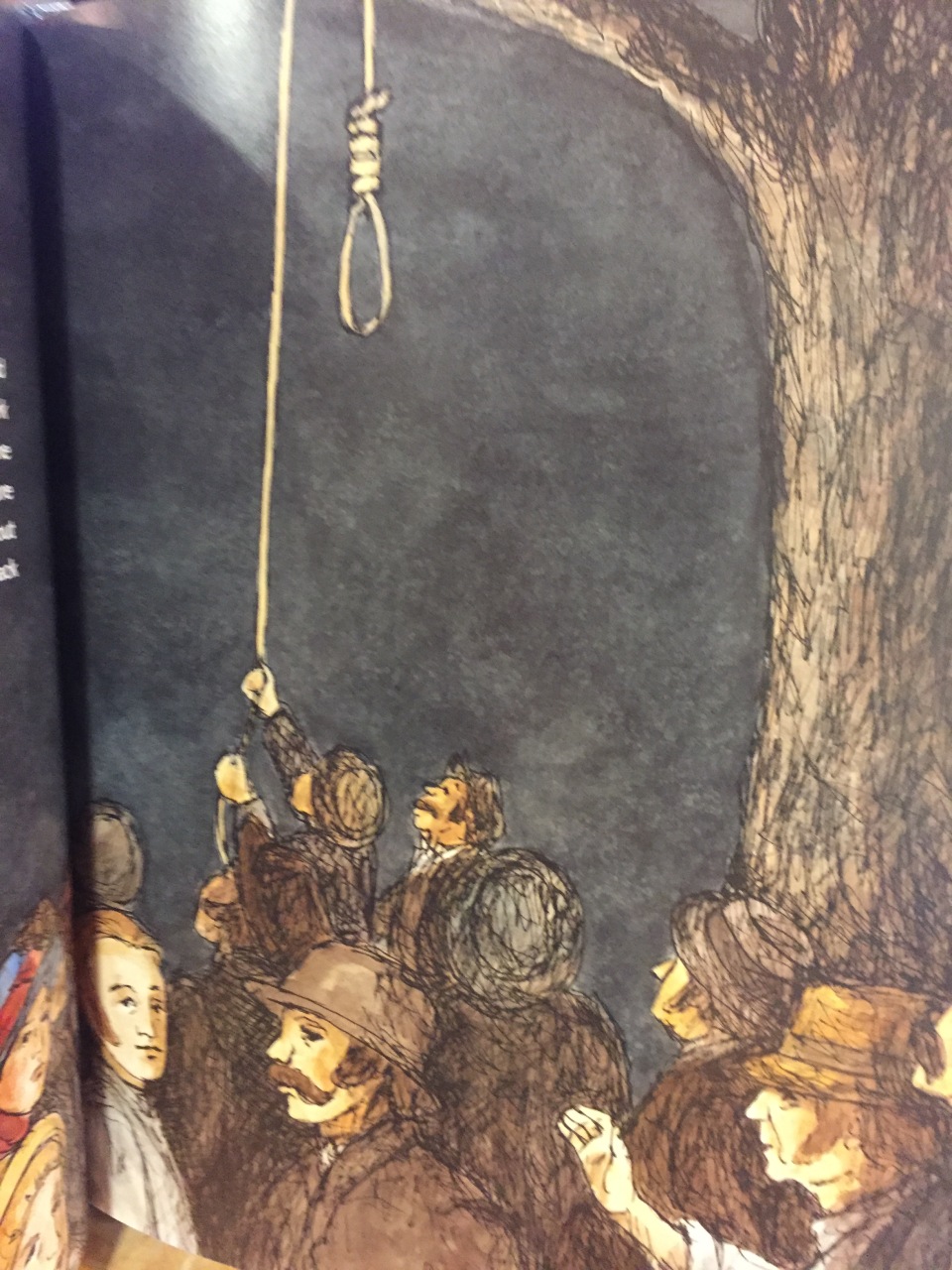

A white mob prepares for a lynching in Myers’ and Christensen’s biography of Ida B. Wells.

Racist incidents are up around the US since the election. The fact that this was true after the 2008 election as well is little comfort; the idea of an increase in racism after an election as a “new normal” is not something to which any country should aspire. However, many people argue that the current climate on racist hate is different, because many of the people being invited to join the new cabinet have made openly racist statements themselves—which may embolden or enable racists to speak (or worse, act) out.

Because the US is not alone in experiencing an increase in racist hate crimes following an election (Britain’s Brexit vote produced a similar uptick), I thought it might be useful to look at children’s literature that deals with a particular kind of racist hate crime: lynching. It’s not an easy topic to explain to children, but it’s one that shows how deep and long a divide the US has had regarding racist crimes, and what can happen when people do and do not speak up against injustice. For these reasons, books about lynching can provide an important voice for social justice campaigners, as well as for victims of race hatred.

The cover of Hinman’s book is more forceful on lynching than most of Hinman’s text.

The first category of books I found about lynching were focused on this social justice campaigning aspect. There are several books about the pioneering reporter, Ida B. Wells, and her attempts to bring light to lynching through her reporting and her writing. Some of these biographies try to discuss lynching in historical terms which—like books about slavery that begin with Ancient Greece or Rome—tend to minimize the racial motivation behind most modern-day lynchings. Eternal Vigilance: The Story of Ida B. Wells-Barnett (2010) by Bonnie Hinman, for example, argues that “In pre-Revolutionary America, lynchings were often beatings rather than killings, and British sympathizers were the usual targets” (44). While this might provide historical background, it also has the effect of suggesting that lynching is just one of those things that most groups have to experience if they have unpopular opinions. Hinman’s book does go on to discuss the lynching of African-Americans more specifically, but it remains couched in a language seemingly designed to give credence to the lynchers. For example, Hinman writes, “The one reason [for an increase in lynching] trumpeted throughout the South was that black men were attacking and raping white women. Southerners were united in their condemnation of the awful crimes allegedly being committed against white women, and felt they couldn’t do less than hunt down and kill the criminals” (45). Despite the use of the word “allegedly,” the construction of these sentences have a “no smoke without fire” suggestion about them, and nowhere in the sentences or paragraphs that precede or follow them does Hinman say that those lynched were often innocent of the “awful crimes” of which they were accused.

Justice is sometimes an abstract concept in Dray’s and Alcorn’s version of Wells’ life.

Hinman’s book is for older readers, but books for younger readers on Ida B. Wells have also been published and because Wells’ lynching campaign was such a huge part of her fame, it cannot be avoided in the books. Philip Dray and Stephen Alcorn’s picture book version of Wells’ life, Yours for Justice, Ida B. Wells: The Daring Life of a Crusading Journalist (2008) is direct, but sparse, in its discussion of lynching. The initial case that led to Wells’ crusade was that of the grocery store owner, Tom Moss. Dray writes, “Tom hoped a judge would understand that they had been trying to protect their property. But before he and his friends could make their case in court, a mob of white men took them out of the jail and murdered them. This kind of execution outside the law was known as lynching” (Dray, n.p.). The illustration by Stephen Alcorn that accompanies this picture is understated and symbolic rather than direct: it shows only a brown hand holding onto a rose. Yours for Justice takes a direct approach in its text on lynching, but withholds a direct image of lynching and does not go into much detail in the text. Dray goes on to write that no one would come forward to accuse the guilty men, “(e)ven though many people knew who had lynched Tom Moss” (n.p.). This text is accompanied by a cigar-smoking white man on one side of the scales of justice, and several skulls, dripping tears, on the other side. The author’s and illustrator’s attitudes on lynching are clear, but indirect.

Myers book is the most direct in its treatment of lynching of all the ones I looked at for child readers.

Walter Dean Myers and Bonnie Christensen, in Ida B. Wells: Let the Truth Be Told (2008), however, take a different approach. Their book about Wells pulls no punches when it comes to lynching, being the only children’s book mentioned here that includes a picture of white people preparing for a lynching. Myers’ text describes lynching as being “killed by angry white mobs” (9) and—rather than talk about the awful potential crimes of African-American people—calls lynching a crime directly. But Let the Truth Be Told also discusses “the sadness and fear caused by the lynchings” (9) in the African-American community, and points out that Wells had to leave Memphis for Chicago because of her writing against lynching. Myers does not suggest Wells followed an easy path, but throughout he gives her character strength through her conviction that her cause is just. Myers quotes Frederick Douglass as well as Wells herself in the book to suggest that justice is a cause worth fighting for. Douglass calls Wells “brave,” and the quotation that Myers uses from Wells’ autobiography seems to be a challenge to readers. In red letters, in larger type than the rest of the page, Myers quotes her saying: “In the past ten years over a thousand black men and women and children have met this violent death at the hands of a white mob. And the rest of America has remained silent.” Black or white, Myers seems to say, you can’t be silent when injustice is done. It’s a lesson we must all, especially now, take to heart.

I had intended to write about the other major category of children’s book that deals with lynching, books about Emmett Till, but I’ve run out of space for today. So stay tuned for that next week . . .