This week I finally got to the Black Power exhibition at the Schomburg Center in New York, which recognizes the impact of Black Power and the Black Panther party during the 1960s and 1970s, both in the US and globally. I was particularly interested in the discussion in the exhibit about children, and have been thinking about this ever since—especially because my week also included a reading of Robin Bernstein’s piece in the New York Times, “Let Black Kids Just be Kids” (https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/26/opinion/black-kids-discrimination.html), and Pam Muñoz Ryan’s Newbery Honor Book, Echo (Scholastic, 2015).

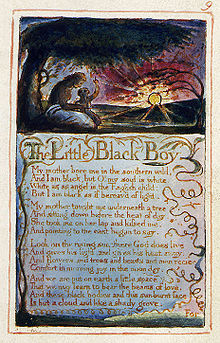

Blake was aware in the 1790s that Black children were not allowed innocence in white society.

Bernstein’s op-ed piece talks about the construction of innocence (presumably in the US, since all her examples are American, but her arguments can be stretched to other countries as well) as having racial connotations, beginning especially in the 19th century. During this period, the romantic notion of the child was as an innocent, blank slate—but only, Bernstein argues, the white child. “The more that popular writers, playwrights, actors and visual artists created images of innocent white children, the more they depicted children of color, especially black children, as unconstrained imps. Over time, this resulted in them being defined as nonchildren,” she writes. While she mentions an exception to this (Harriet Beecher Stowe’s representation of Topsy, which was then destroyed by the popular theatre versions of Stowe’s book), and I would argue that there are other counter-examples (William Blake’s version of innocence, for example, was not confined to white children—although as his poetry makes clear, Black children’s innocence was confounded by white society), her main point is sound. Children who are not white are often seen in white-dominated societies as threatening.

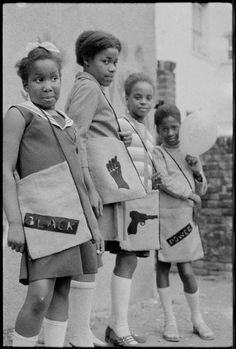

Kenlock’s Black Panther girls are innocent of wrong-doing, but not innocent of injustice.

I looked back at the photos I had taken in the Black Power exhibit, most of which were either pictures of children or pictures of Black Arts poetry. None of the children in the photos were smiling, and many of them could be seen as provocative, with the children looking defiantly at the camera adorned with Black Power symbols. These photographs were not taken by white photographers who saw a threat, but Black and white photographers who saw a possibility. White photographer Stephen Shames’ image of a Black boy in a white Angela Davis t-shirt was designed, along with his other Black Panthers photographs, to show that “‘black pride’ was not based on denigrating whites, but on showing the black community that they were in control of their own destiny” (http://www.stephenshames.com/projects/black-panther-party). Black photographer Neil Kenlock’s photograph of Black Power girls in Brixton, which was part of the “Stan Firm Inna Inglan” exhibition I saw at the Tate in London, was also reproduced here to showcase global Black Pride. But whether you looked at these photos and saw strength or threat, it is difficult to see the children in these photos as innocent, in the sense of innocent as someone who is unknowing, a blank slate in John Locke’s definition. You can’t be innocent if you are aware of injustice.

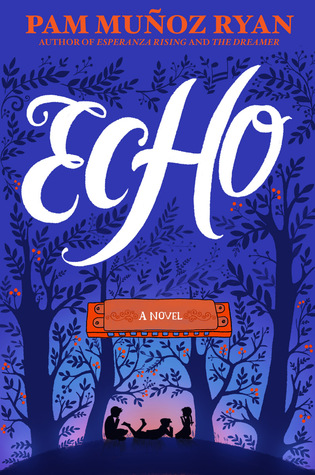

Even music is not innocent of understanding injustice in Ryan’s novel that connects children across time and place.

And this is why I found Pam Muñoz Ryan’s Echo so compelling. The story is really multiple stories, across time and distance and even genre, woven together through the medium of wars (both WWI and WWII) and a harmonica that is owned by multiple child characters. The harmonica, as an instrument, is not a random choice. Ryan takes pains to indicate how music connects us all; one of her characters comments, “Music does not have a race or a disposition . . . Every instrument has a voice that contributes. Music is a universal language” (86) and this sentiment is echoed throughout the novel by different characters. But the speech made here is in response to another character denigrating the harmonica as an instrument. Music is not all innocent and even an instrument can be culpable. Elisabeth is in the Hitler Youth, and the Hitler Youth thinks that the harmonica is “offensive” (85) because it is used to play “Unacceptable music . . . Negro music. Jazz. It’s considered degenerate” (86). Her brother Friedrich, who is Ryan’s main character in this particular story, knows this is nonsense; music is innocent in the sense that it has not done anything wrong. But the harmonica and Friedrich are only innocent in this one sense of the term. They are not the unknowing kind of innocent. Friedrich may not be Jewish, but he is under threat, both for speaking against injustice and for having a physical “deformity”—a birthmark—that may get him confined to an insane asylum or worse in Nazi Germany. The harmonica, which is a somewhat magical version of a regular harmonica, “knows” about sadness, and can play it.

This famous photo from WWII, which appeared in Life magazine, has often been used as a symbol of an innocent boy caught up in fascism. But just because he’s done nothing to deserve a gun being pointed at him, doesn’t mean he doesn’t understand justice.

The knowingness of the harmonica is explained in the next of Ryan’s interconnected stories, in which the Irish-American Mike is taught to play the harmonica by the African-American Mr. Potter. When Mr. Potter first plays, Mike is fascinated and asks him about the sound he gets the harmonica to make. Mr. Potter explains, “blues music is about all the trials and tribulations people got in their hearts from living. . . . Blues is a song begging for its life” (293). Mike has not done anything wrong by becoming an orphan, but he is aware of the injustice that keeps food out of his and other children’s mouths in the orphanage—so he too can play the innocent/not-innocent blues on the harmonica. Similarly, the next owner of the harmonica, Ivy Lopez, is innocent of wrongdoing but is still sent to a crumbling and understocked school because of her Mexican heritage. This not only allows her to play the blues, but to understand the injustice done to another: she exposes the wrong treatment and suspicion of Japanese-Americans who have been interned.

Bernstein’s article ends with a slightly mixed message, arguing that all children should be seen as innocent but also that innocence should not be the focus—rather we should look at whether children are being treated justly. I think most children should be seen as innocent of wrong-doing, because most children are; however, I don’t think any children—Black, white, Latina, Asian, any children—should be the unknowing kind of innocent. We should not only ensure that children are being treated justly, we should teach them how to fight for justice for themselves and others. Because only when everyone is working for justice will we ever achieve it.